‘People of today take the railways for granted as they take the sea and the sky; they were born into a railway world, and they expect to die in one’ – H.G. Wells

As the London Underground recently reached its 150th birthday, the 9th of January marking the first underground journey between Paddington and Farringdon, it is time for a reappraisal of an transit system so entrenched in the daily lives of Londoners that it has sunk into the background of everyday life. One’s experience of the underground is imbued with a sort of weird mix of pathos and bathos; a journey on the underground, it seems, is, at least for those who live and work in London, the zero point of humdrum against which the more exciting moments of life is now measured against. As someone who doesn’t live in London perhaps I am able to have a slightly different perspective, not having to rely on the system on a daily basis, and not associating it with the drudgery of work. As a visitor to the city, I have come to view the underground somewhat romantically, loving its urbanity and its simplicity, not to mention its history. Perhaps I also find something strangely attractive in its everydayness, and the way that that very everydayness or banality contains such an intriguing history, that something so apparently meaningless could seem to be so drenched in meaning. Of course, it should also be noted that whenever I have used the tube, it has been to visit friends, or to explore the city like some wannabe flaneur, rather than a weary eyed commuter. Having said that, there are plenty of people I know who do not live in London who regard the Underground with a similar distaste as those who use it every day. For these people, its perceived dirtiness and the claustrophobic quality of its environment is a metonym for the city itself.

The Underground could hardly be said to be perfect. It might well be true, as many people claim, that in comparison with other urban transit systems, the Underground, in terms of quality, comfort and price ranks fairly poorly. However, this does not mean that its value is immense, and I do not simply mean its value to tourists and commuters but also its cultural and experiential influence, something which has largely been ignored. Recently travelling from Paddington to Victoria on the District line, one of the older lines of the system, I tried to imagine the experience of excitement and wonder of those travelling between Paddington and Farringdon in 1863, moving only through darkness, only to arrive in dimly lit stations hidden beneath the surface of the city. Unlike the trains of today, the earliest trains used beneath London were steam powered, meaning that the train would have been moving through a tube leaving behind a poisonous zephyr (smelling and tasting of sulphur) caught within the tube in which it moved, an even more strange experience for those inside the carriages. For those people who took the first train journeys in the earliest years of the underground, it is probably safe to say that the experience would have been incredibly novel, if not also frightening and probably even disgusting. What is most interesting about the novelty of the Underground in its infancy is the way in which it would have been seen, represented and talked about in so many different ways. In Underground Writing: The London Tube from George Gissing to Virginia Woolf (Liverpool: University of Liverpool Press, 2010), David Welsh writes;

It was a sensation from the first day of construction, triggering outraged opposition, mockery and disbelief at the notion of running a steam train under the streets of the capital. It opened up a subsurface world that had hitherto been populated by sewers, water and gas pipes, the electric telegraph, plague pits and crypts, giving London an underworld whose only equivalent seemed to be the Parisian catacombs.

The novelty of the underground was as much a threat as it was something exciting and pleasurable. It was situated, in the popular imagination at least, between the absolutely modern and something much older, residing somewhere in medieval theology or ancient myths. Welsh sees the association between this decidedly modern infrastructure and the ancient and mythical (contemporary writers using the language of the underworld, there reference points including Hades and the Styx) as a defensive strategy: ‘the ways in which the most modern of Victorian enterprises became embedded in layers of classical myth may have offered a vocabulary that deflected the shattering impact of modernity.’ Around the underground there merged clustered both the grueling reality of nineteenth century capitalist modernity, and also a certain respite from it, a world that was distinctly other.

If the underground was then shocking and exhilarating, perhaps a metaphor of a historical moment that did not know whether to look backwards or forwards, today it is nothing more than a resource – if it ‘means’ anything at all, then that meaning is empty, something easily used by ad men perhaps, able to suggest vague signifiers of urbanity or Britishness. For Welsh ‘the tube is a pervasive cultural metaphor, seen by some as representing the postmodern condition through its identification as a place where people’s lives intersect, relationships are formed and the urban world defined.’ This is perhaps overstatement of the tube’s signifying power, at least in relation to our everyday lives and mainstream popular culture. Although the metaphorical power of the tube might be used by writers of fiction for various purposes, it is unlikely that, even if we are to regard the tube as all of those things, as Welsh describes, this metaphorical power is largely disavowed, or just simply forgotten.

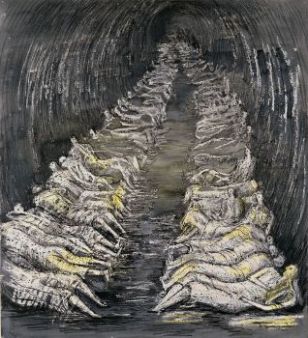

However, the beauty of the tube, and its brilliance as a signifier of modernity, another reality that makes the reality of life in London possible, both practically and imaginatively, is worth remembering. Indeed, adding to its power as a metaphor or signifier, one need only think to the role the Underground played during the Blitz to see how the Underground has a special significance within the history of the city that goes beyond the purely symbolic and the official. In this case the underground’s meaning became bound up with the bodies of Londoners, the lives of those who would have been lost to German bombs. Here the subterranean darkness and dirt that one might usually associate with the underground and its stations becomes paradoxically a subterranean refuge.

Of course it is difficult, and perhaps just daft to look at the world with dazed child like wonder everyday. Indeed, the celebrations marking the Underground’s anniversary have been well publicised, so one can hardly claim that the Tube’s history is completely forgotten and disregarded. Even as I write, I have just seen that there has been a tube related £2 coin produced as a further way to mark the anniversary (they look quite pretty, as coins go). However, this is not to say that we can’t look at the tube with a certain detachment and to be perceptive to its sheer strangeness. The tube has a history that cannot be separated from our vision and understanding of London, even our conception of the modern city in general. No major city would be possible without a functioning transit system – and for the most part, such transit systems run beneath street level. We are the very people that H.G. Wells is writing about in the quote above – people who take the railways for granted. Yet there is also something even more interesting at play in his words, when read from our own perspective; his words seem somehow quaint, and if they somehow prophesy twenty first century urban life, life that is completely dependent on the restless invention of technology while at the same time being completely oblivious to such a fact, they are clearly not a part of that world. For to speak with such enchantment about disenchantment locates Wells and the historical moment from which he writes in a decidedly different world from our own, a world in which disenchantment cannot be articulated without being tinged with bathos or ennui.